A life in color and courage

Paint, letters, friendship, and a restless search for light.

Table of Contents

From Brabant to Amsterdam: beginnings

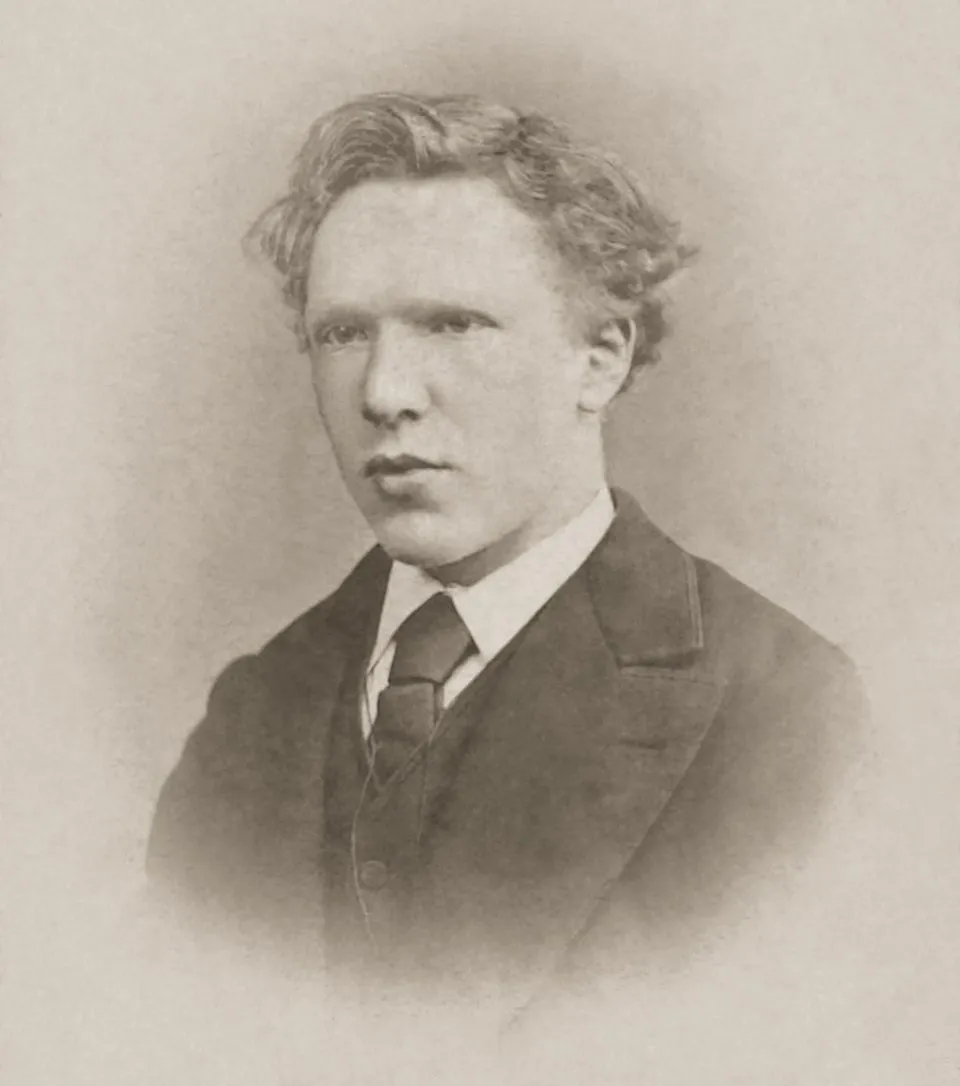

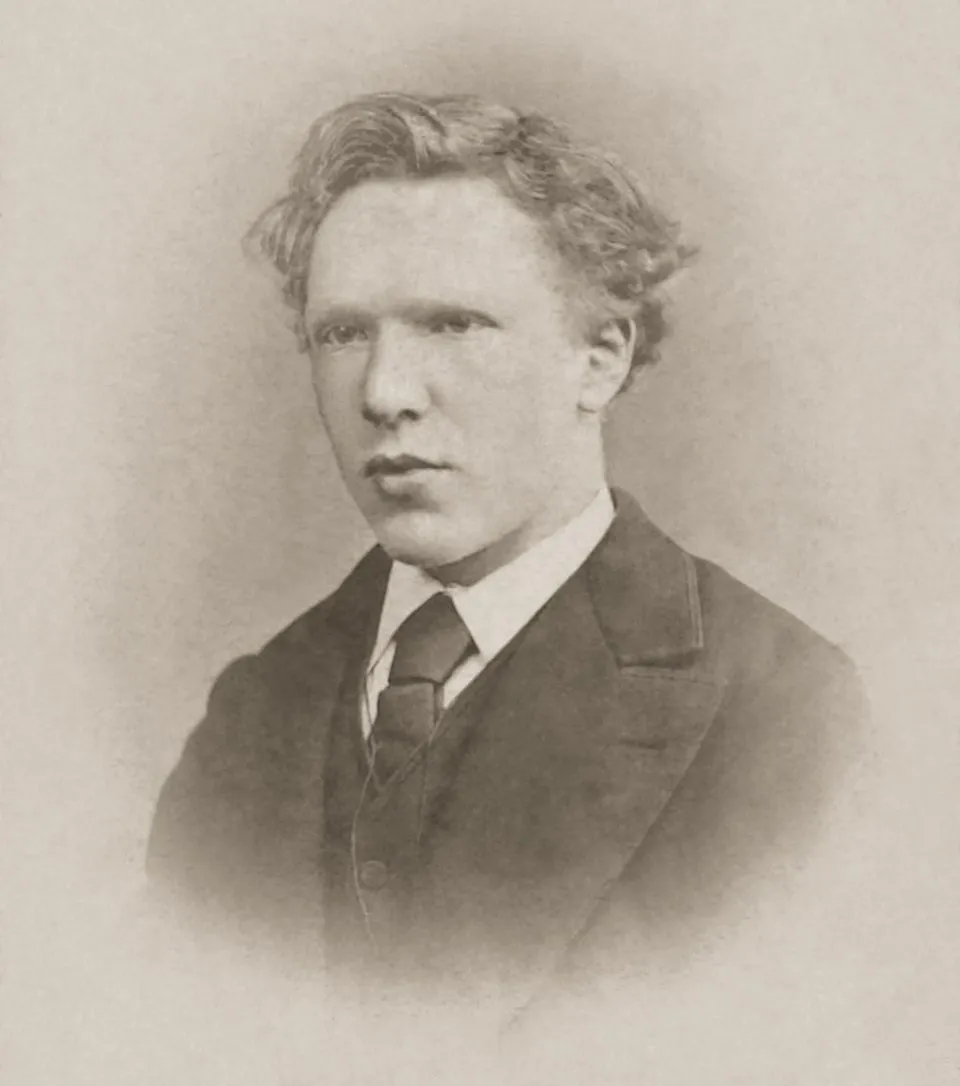

Vincent van Gogh’s story starts in the Netherlands, where he wrestled with vocation and purpose before he ever picked up a brush with intent. He tried books, teaching, and even ministry, always drawn to people on the margins — field workers, weavers, the poor — whose lives carried a gravity he felt in his bones. When he began to paint in earnest, the palette was earthy and dark, the forms rough‑hewn, the mood sincere. Works like The Potato Eaters show a young artist searching for truth rather than charm, building skill stroke by stroke, stubborn as winter and tender as lamplight.

Those early Dutch years taught him patience and structure — how tones build volumes, how hands tell stories, how everyday objects dignify the people who use them. The move to art was not a leap but a series of small crossings, guided by letters to his brother Theo, who answered with practical help and unwavering belief. By the time Vincent turned toward color in Paris, he carried those foundations with him, ready to learn fast and change forever.

Paris light: color learned quickly

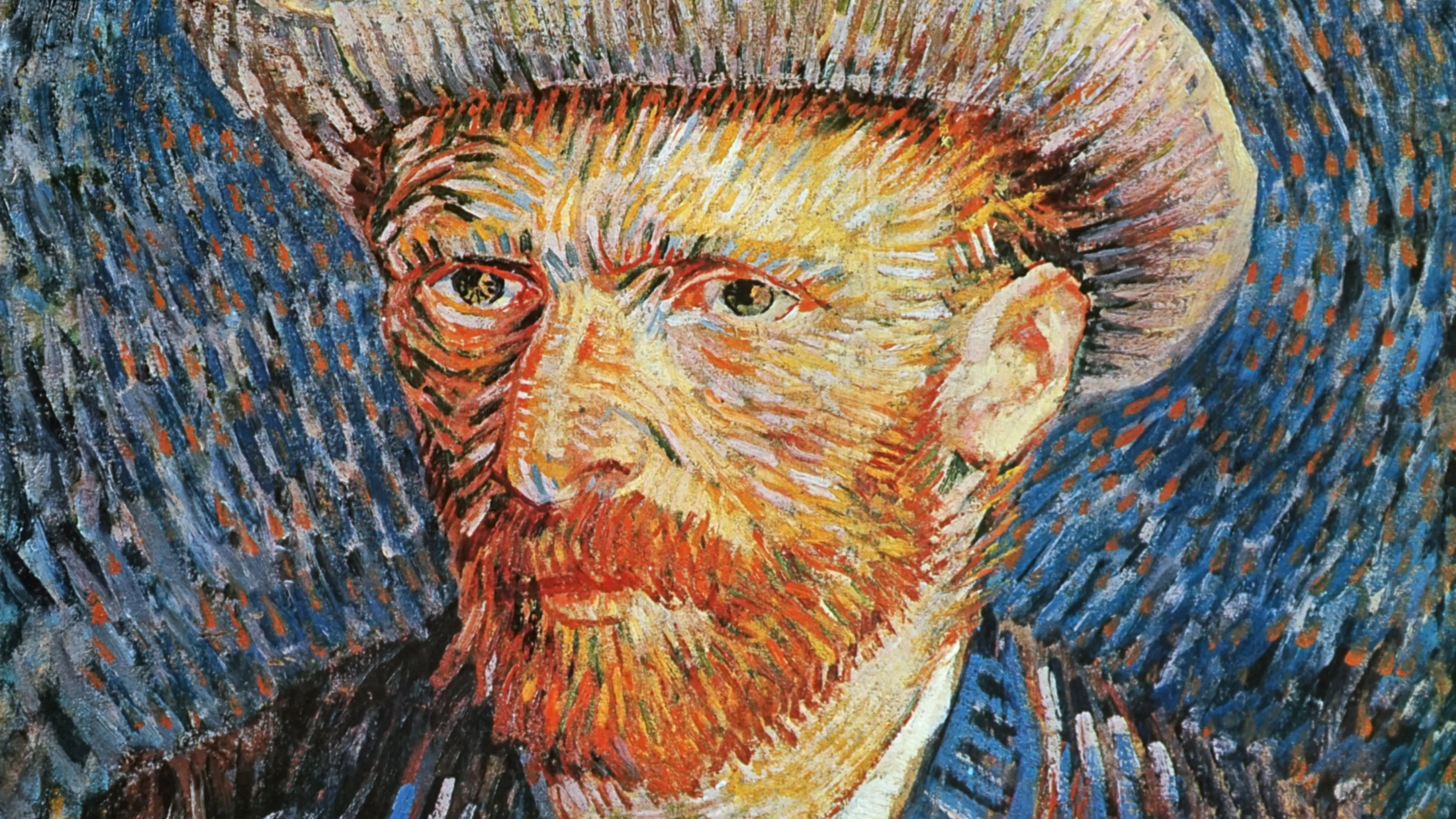

In Paris, everything shifted. Vincent encountered Impressionists and Neo‑Impressionists, Japanese prints, and a new way of seeing that treated color as living air rather than surface skin. He studied the quick light on café terraces, wind through trees on the Butte, the violet of shadows that are never simply black. He painted flowers by the armful to learn complementary contrasts, self‑portraits to test palettes and resolve, and sunlit streets to practice a fresher stroke.

He learned by doing — furiously — and he wrote to Theo about it all: pigment costs, canvases reused, techniques tried and discarded. The city gave him friendships, rivalries, an open window; his courage opened the rest. Paris did not soften him; it taught him how to aim his intensity into color.

Arles and the Yellow House

Arles was a wager on sunlight — on the notion that a clearer sky could clarify vision itself. Vincent rented the Yellow House and dreamed of an artists’ studio in the South. With every orchard and café, every wheat field and lamplit street, he built a language of vibrant greens, cobalt nights, chrome yellows that hum just shy of music. He wasn’t painting scenery; he was painting attention — the way a chair can feel like a person, a bedroom like a life held together by need and care.

When Paul Gauguin joined him, friendship and friction sparked. They argued about method and meaning, about drawing from memory or from life. The collaboration didn’t last, but its heat forged some of Vincent’s most unforgettable paintings. The dream of a shared studio faltered; the work did not. He kept going, with stubborn tenderness, one canvas to the next.

Saint‑Rémy and the healing studio

At Saint‑Rémy, art and rest had to share the same house. Vincent painted from his window and in the gardens, giving the wind a visible shape, letting cypresses twist like thought itself. He returned to subjects he loved — olive trees, irises — and found solace in rhythm, in repeated forms, in blue’s many ways of being blue.

Illness did not define these paintings; if anything, they demonstrate an astonishing clarity of craft under pressure. The brushwork spikes and softens, the compositions hold firm, and the color sings. The studio was also a refuge, a steady table, a place to be useful to himself and to others who would come after.

Auvers: urgency and open skies

In Auvers‑sur‑Oise, time felt thin and bright. Vincent painted fast and with purpose — gardens, cottages, church, fields, skies that carry weather and wonder in equal measure. The sense of urgency is palpable, but so is the order: each canvas is built with care, the composition balanced, the color deliberate.

These final months were not only struggle; they were a harvest of everything learned — drawing, color, patience, empathy. The works glow with a thinking hand, leaving us with a humane vision that refuses to look away from either beauty or difficulty.

Theo, the letters, and a brother’s promise

The letters are the museum’s quiet heart. Written mostly to Theo, they move between pigment orders and philosophy, between loneliness and hope, between a day’s work and a life’s aim. We learn how carefully Vincent looked, how he built pictures from memory and sensation, how friendship braced him against isolation.

Theo’s belief kept canvases, paints, and courage within reach. After both brothers died within months of each other, Theo’s wife, Jo van Gogh‑Bonger, carried the promise forward — cataloguing, exhibiting, and tirelessly advocating for the work. Without her, this collection would be scattered, the story harder to hear.

A museum takes shape: collection & architecture

Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum opened in 1973, gathering the core family collection into a space designed for light and clarity. Gerrit Rietveld’s building offers clean lines and gentle circulation; the later Kisho Kurokawa wing adds a luminous, glass‑fronted volume for exhibitions and events. Together they make a place where looking feels unhurried and precise.

The collection remains intimate in spirit even as it is world‑famous: paintings and drawings in dialogue with letters, studies beside breakthroughs, friends and influences framing Vincent’s own fierce trajectory.

Conservation, research, and close looking

Conservation labs study pigments, canvases, and varnishes to understand how the works were made and how best to care for them. Scientific images reveal underdrawings, changes of mind, and the material story of each painting.

Research publications and exhibitions share these findings with the public, inviting visitors to look more slowly — to see not just the picture, but the choices that brought it into being.

Exhibitions, friendships, and influences

Rotating exhibitions pair Van Gogh with artists he admired and challenged — Millet’s humility, Gauguin’s symbolism, Monet’s light, Japanese ukiyo‑e prints. These dialogues sharpen what is unique in Vincent’s work while situating him in a shared, evolving conversation.

The museum’s programming also highlights friendships and networks — how ideas move through letters, studios, and city streets, and how art, at its best, is a social act of attention.

Tickets, passes & planning tips

Timed-entry tickets are required and popular days sell out. Book early for morning or late afternoon if you prefer quieter rooms.

Some city passes require an extra time-slot reservation and may not cover the full ticket price; always check the latest terms.

Accessibility, families, and easy visits

Elevators, accessible routes, and seating help make the visit comfortable. Family tools and audio tours engage younger visitors without overwhelming them.

Arrive a few minutes before your slot, travel light, and follow staff guidance — simple steps that keep the focus on the art.

Museumplein: what’s nearby

The Van Gogh Museum sits beside the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk. The green expanse of Museumplein is perfect for a relaxed break between galleries.

Cafés and tram connections are close by; combine your visit with a canal cruise or a stroll through the Canal Belt.

Why Van Gogh still matters

Because the paintings look back at us — not as puzzles to solve, but as companions in the work of being human. Van Gogh made ordinary things radiant and difficult feelings bearable, insisting that looking closely is a kind of care.

In Amsterdam, the collection gathers this courage into a single place. You leave feeling a little more awake to color, to people, to the world — and perhaps to your own capacity for persistence and kindness.

Table of Contents

From Brabant to Amsterdam: beginnings

Vincent van Gogh’s story starts in the Netherlands, where he wrestled with vocation and purpose before he ever picked up a brush with intent. He tried books, teaching, and even ministry, always drawn to people on the margins — field workers, weavers, the poor — whose lives carried a gravity he felt in his bones. When he began to paint in earnest, the palette was earthy and dark, the forms rough‑hewn, the mood sincere. Works like The Potato Eaters show a young artist searching for truth rather than charm, building skill stroke by stroke, stubborn as winter and tender as lamplight.

Those early Dutch years taught him patience and structure — how tones build volumes, how hands tell stories, how everyday objects dignify the people who use them. The move to art was not a leap but a series of small crossings, guided by letters to his brother Theo, who answered with practical help and unwavering belief. By the time Vincent turned toward color in Paris, he carried those foundations with him, ready to learn fast and change forever.

Paris light: color learned quickly

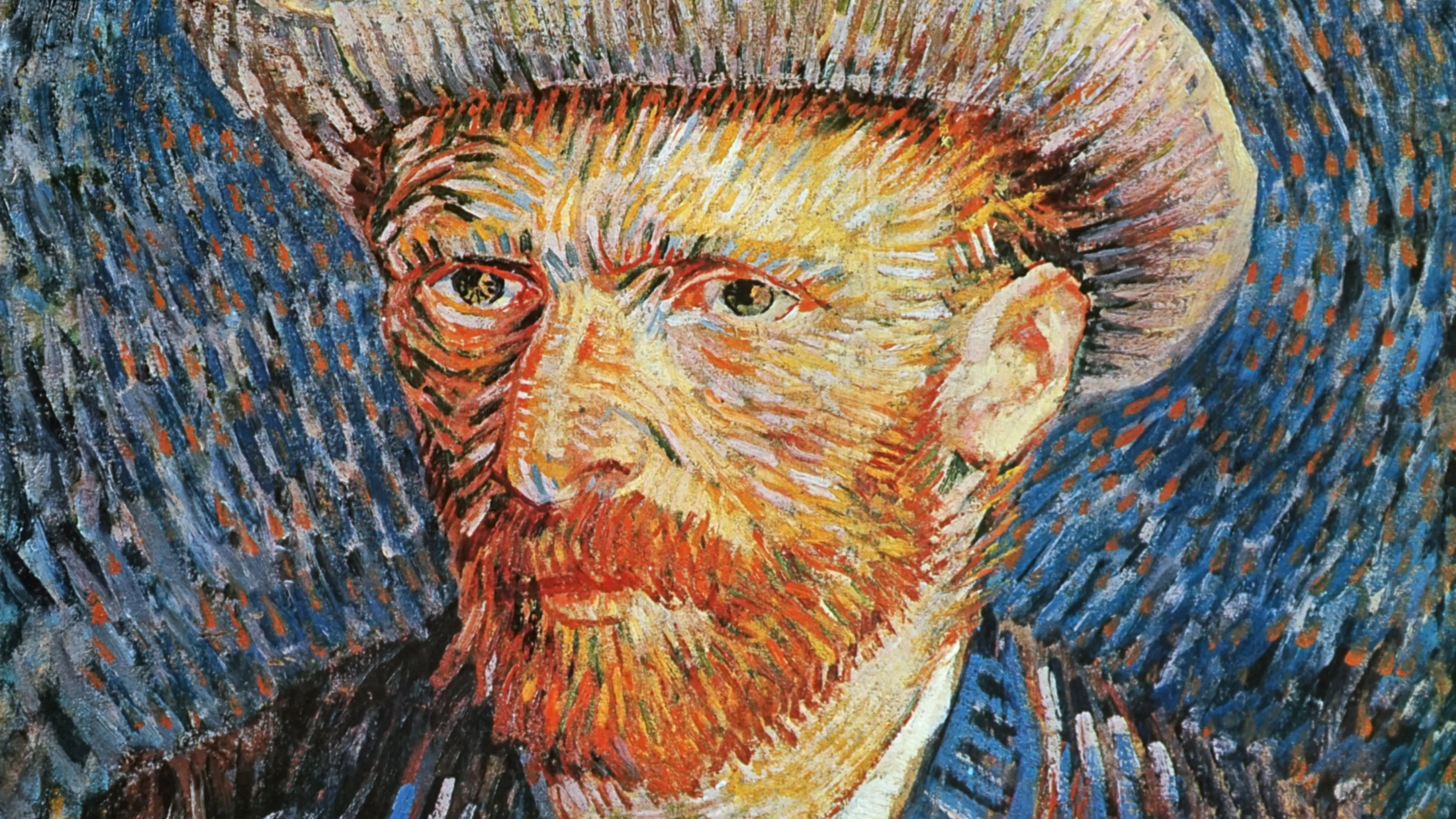

In Paris, everything shifted. Vincent encountered Impressionists and Neo‑Impressionists, Japanese prints, and a new way of seeing that treated color as living air rather than surface skin. He studied the quick light on café terraces, wind through trees on the Butte, the violet of shadows that are never simply black. He painted flowers by the armful to learn complementary contrasts, self‑portraits to test palettes and resolve, and sunlit streets to practice a fresher stroke.

He learned by doing — furiously — and he wrote to Theo about it all: pigment costs, canvases reused, techniques tried and discarded. The city gave him friendships, rivalries, an open window; his courage opened the rest. Paris did not soften him; it taught him how to aim his intensity into color.

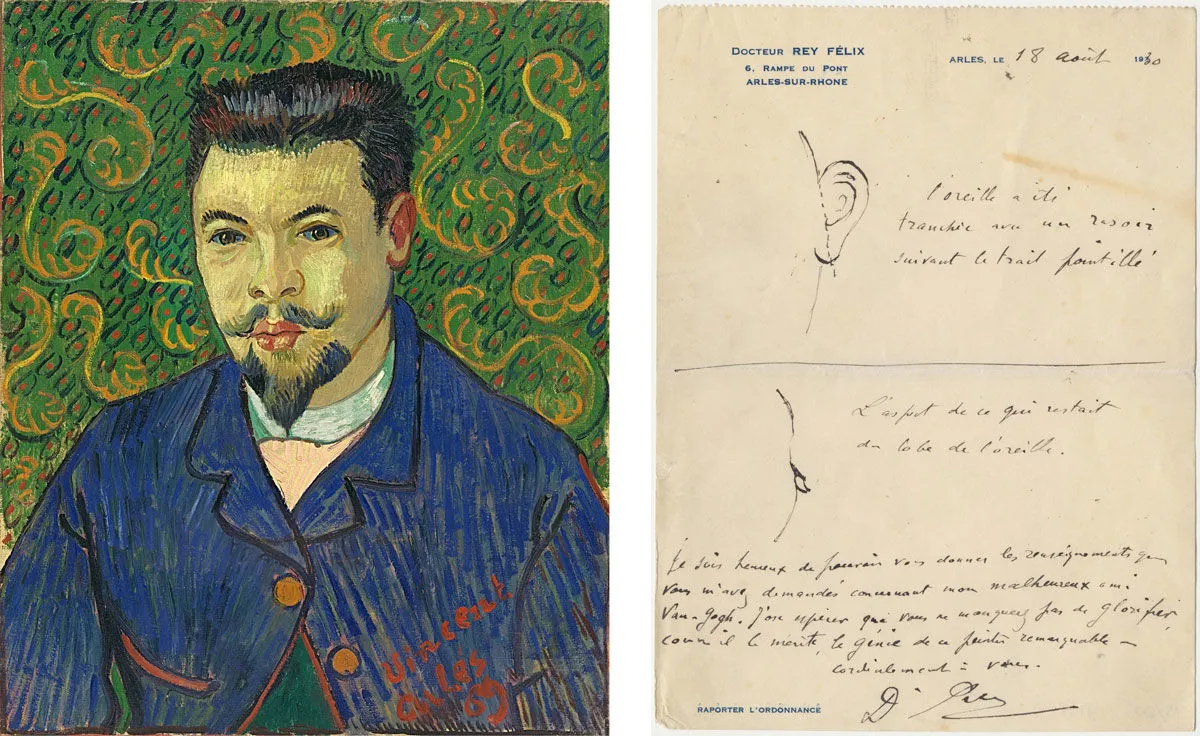

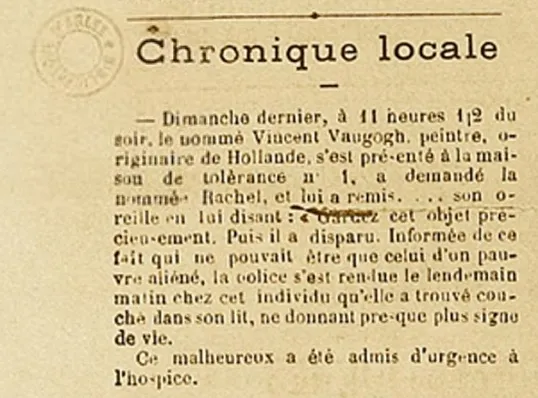

Arles and the Yellow House

Arles was a wager on sunlight — on the notion that a clearer sky could clarify vision itself. Vincent rented the Yellow House and dreamed of an artists’ studio in the South. With every orchard and café, every wheat field and lamplit street, he built a language of vibrant greens, cobalt nights, chrome yellows that hum just shy of music. He wasn’t painting scenery; he was painting attention — the way a chair can feel like a person, a bedroom like a life held together by need and care.

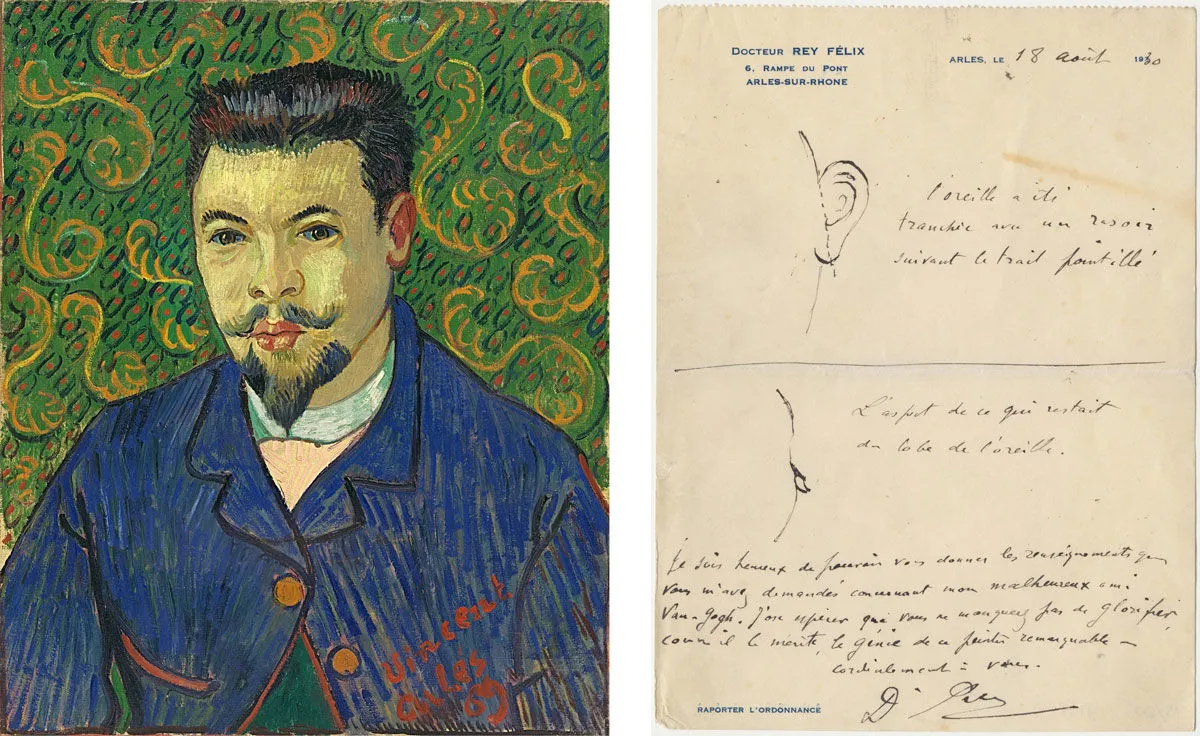

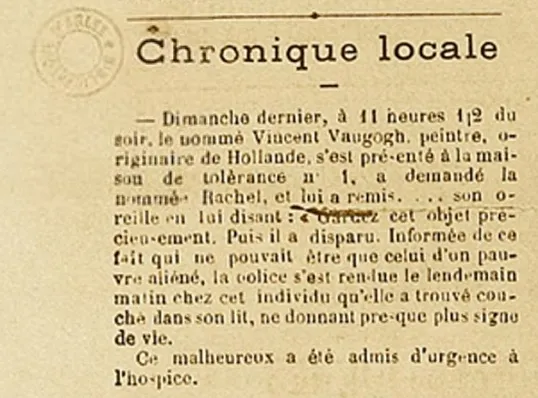

When Paul Gauguin joined him, friendship and friction sparked. They argued about method and meaning, about drawing from memory or from life. The collaboration didn’t last, but its heat forged some of Vincent’s most unforgettable paintings. The dream of a shared studio faltered; the work did not. He kept going, with stubborn tenderness, one canvas to the next.

Saint‑Rémy and the healing studio

At Saint‑Rémy, art and rest had to share the same house. Vincent painted from his window and in the gardens, giving the wind a visible shape, letting cypresses twist like thought itself. He returned to subjects he loved — olive trees, irises — and found solace in rhythm, in repeated forms, in blue’s many ways of being blue.

Illness did not define these paintings; if anything, they demonstrate an astonishing clarity of craft under pressure. The brushwork spikes and softens, the compositions hold firm, and the color sings. The studio was also a refuge, a steady table, a place to be useful to himself and to others who would come after.

Auvers: urgency and open skies

In Auvers‑sur‑Oise, time felt thin and bright. Vincent painted fast and with purpose — gardens, cottages, church, fields, skies that carry weather and wonder in equal measure. The sense of urgency is palpable, but so is the order: each canvas is built with care, the composition balanced, the color deliberate.

These final months were not only struggle; they were a harvest of everything learned — drawing, color, patience, empathy. The works glow with a thinking hand, leaving us with a humane vision that refuses to look away from either beauty or difficulty.

Theo, the letters, and a brother’s promise

The letters are the museum’s quiet heart. Written mostly to Theo, they move between pigment orders and philosophy, between loneliness and hope, between a day’s work and a life’s aim. We learn how carefully Vincent looked, how he built pictures from memory and sensation, how friendship braced him against isolation.

Theo’s belief kept canvases, paints, and courage within reach. After both brothers died within months of each other, Theo’s wife, Jo van Gogh‑Bonger, carried the promise forward — cataloguing, exhibiting, and tirelessly advocating for the work. Without her, this collection would be scattered, the story harder to hear.

A museum takes shape: collection & architecture

Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum opened in 1973, gathering the core family collection into a space designed for light and clarity. Gerrit Rietveld’s building offers clean lines and gentle circulation; the later Kisho Kurokawa wing adds a luminous, glass‑fronted volume for exhibitions and events. Together they make a place where looking feels unhurried and precise.

The collection remains intimate in spirit even as it is world‑famous: paintings and drawings in dialogue with letters, studies beside breakthroughs, friends and influences framing Vincent’s own fierce trajectory.

Conservation, research, and close looking

Conservation labs study pigments, canvases, and varnishes to understand how the works were made and how best to care for them. Scientific images reveal underdrawings, changes of mind, and the material story of each painting.

Research publications and exhibitions share these findings with the public, inviting visitors to look more slowly — to see not just the picture, but the choices that brought it into being.

Exhibitions, friendships, and influences

Rotating exhibitions pair Van Gogh with artists he admired and challenged — Millet’s humility, Gauguin’s symbolism, Monet’s light, Japanese ukiyo‑e prints. These dialogues sharpen what is unique in Vincent’s work while situating him in a shared, evolving conversation.

The museum’s programming also highlights friendships and networks — how ideas move through letters, studios, and city streets, and how art, at its best, is a social act of attention.

Tickets, passes & planning tips

Timed-entry tickets are required and popular days sell out. Book early for morning or late afternoon if you prefer quieter rooms.

Some city passes require an extra time-slot reservation and may not cover the full ticket price; always check the latest terms.

Accessibility, families, and easy visits

Elevators, accessible routes, and seating help make the visit comfortable. Family tools and audio tours engage younger visitors without overwhelming them.

Arrive a few minutes before your slot, travel light, and follow staff guidance — simple steps that keep the focus on the art.

Museumplein: what’s nearby

The Van Gogh Museum sits beside the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk. The green expanse of Museumplein is perfect for a relaxed break between galleries.

Cafés and tram connections are close by; combine your visit with a canal cruise or a stroll through the Canal Belt.

Why Van Gogh still matters

Because the paintings look back at us — not as puzzles to solve, but as companions in the work of being human. Van Gogh made ordinary things radiant and difficult feelings bearable, insisting that looking closely is a kind of care.

In Amsterdam, the collection gathers this courage into a single place. You leave feeling a little more awake to color, to people, to the world — and perhaps to your own capacity for persistence and kindness.